Back عمارة نبطية Arabic নাবাতীয় স্থাপত্য Bengali/Bangla Arquitectura nabatea Spanish Architecture nabatéenne French Architettura nabatea Italian

| Part of a series on |

| Arabic culture |

|---|

|

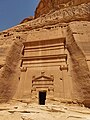

Nabatean architecture (Arabic: اَلْعِمَارَةُ النَّبَطِيَّةُ; al-ʿimarah al-nabatiyyah) refers to the building traditions of the Nabateans (/ˌnæbəˈtiːənz/; Nabataean Aramaic: 𐢕𐢃𐢋𐢈 Nabāṭū; Arabic: ٱلْأَنْبَاط al-ʾAnbāṭ; compare Akkadian: 𒈾𒁀𒌅 Nabātu; Ancient Greek: Ναβαταῖος; Latin: Nabataeus), an ancient Arab people who inhabited northern Arabia and the southern Levant. Their settlements—most prominently the assumed capital city of Raqmu (present-day Petra, Jordan)—gave the name Nabatene (Ancient Greek: Ναβατηνή, Nabatēnḗ) to the Arabian borderland that stretched from the Euphrates to the Red Sea. Their architectural style is notable for its temples and tombs, most famously the ones found in Petra. The style appears to be a mix of Mesopotamian, Phoenician and Hellenistic influences modified to suit the Arab architectural taste.[1] Petra, the capital of the kingdom of Nabatea, is as famous now as it was in the antiquity for its remarkable rock-cut tombs and temples. Most architectural Nabatean remains, dating from the 1st century BC to the 2nd century AD, are highly visible and well-preserved, with over 500 monuments in Petra, in modern-day Jordan, and 110 well preserved tombs set in the desert landscape of Hegra, now in modern-day Saudi Arabia.[2] Much of the surviving architecture was carved out of rock cliffs, hence the columns do not actually support anything but are used for purely ornamental purposes. In addition to the most famous sites in Petra, there are also Nabatean complexes at Obodas (Avdat) and residential complexes at Mampsis (Kurnub) and a religious site of et-Tannur.

The accomplishments the Nabateans had with hydraulic technology forged the power and the increase of the standard of living of the residents living in the capital of the ancient Nabataean kingdom. Cited among the most powerful of pre-islamic Arabia, Petra does not hold its fame and its prosperity only by its buildings dug and sculpted in the rocks of the surrounding mountains; it is above all through its extraordinary hydraulic system, built over the centuries, that Petra was able to develop in the middle of an inhospitable desert and become a strategic crossroad for which stood halfway between the opening to the Gulf of Akaba and the Dead Sea at a point where the Incense Route from Arabia to Damascus was crossed by the overland route from Petra to Gaza.[3] This position gave the Nabateans a hold over the trade along the Incense Route.[3]

Although the Nabataean kingdom became a client state of the Roman Empire in the first century BC, it was only in 106 AD that it lost its independence. Petra fell to the Romans, who annexed Nabataea and renamed it as Arabia Petraea. Petra's importance declined as sea trade routes emerged. The earthquake of the year 363 caused an end to the development of the city and to the maintenance of the hydraulic network that survived the epoch of the Roman rule, mainly the storage tanks and the aqueducts, part of which was destroyed and no longer allowed transport water to the various buildings and the partially destroyed thermal baths. In the Byzantine era several Christian churches were built, but the city continued to decline, and by the early Islamic era it was abandoned except for a handful of nomads. It remained unknown until it was rediscovered in 1812 by Johann Ludwig Burckhardt.[4][5][6]

- ^ "Nabataean Architectural Identity and its Impact on Contemporary Architecture in Jordan", Dirasat, Engineering Sciences.

- ^ "Nabataean Kingdom and Petra | Essay | the Metropolitan Museum of Art | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History".

- ^ a b Eckenstein, Lina (2005). A History of Sinai. Adamant Media Corporation, p. 86.

- ^ Glueck, Grace (17 October 2003). "ART REVIEW; Rose-Red City Carved From the Rock". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 28 December 2017. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- ^ Martha Sharp Joukowsky. Petra the Great Temple exclavation 2006 ADAJ Report. § Dating the Baths.

- ^ "Petra lost and found". History Magazine. 2018-02-09. Archived from the original on August 6, 2020. Retrieved 2021-01-15.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search